![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

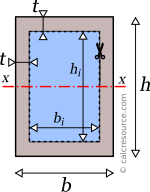

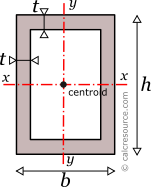

where t , the thickness of the walls.

The moment of inertia (second moment of area) of a rectangular tube section, in respect to an axis x passing through its centroid, and being parallel to its base b, can be found by the following expression:

where b is the section width, and specifically the dimension parallel to the axis, and h is the section height (more specifically, the dimension perpendicular to the axis), b_i , the internal width and h_i the internal height. Because the moment of inertia of a solid rectangle is b h^3\over12 , the moment of inertia of the rectangular tube, can be seen as a difference between two rectangular areas: an external rectangle with dimensions b , h , minus an internal one, with dimensions b_i , h_i .

Similarly, the moment of inertia (second moment of area) of a rectangular tube, around a centroidal axis y, perpendicular to base b, can be found, by an equation similar to the previous one but with interchanged the width and height dimensions:

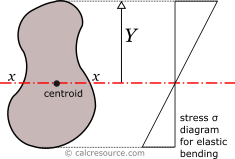

The moment of inertia (second moment or area) is used in beam theory to describe the rigidity of a beam against flexural bending. The bending moment M applied to a cross-section is typically related to the moment of inertia of the cross-section with the following equation:

M = E\times I \times \kappa

where E is the Young's modulus, a property of the material, and \kappa the curvature of the beam due to the applied load. Therefore, it can be seen from the former equation, that when a certain bending moment M is applied to a beam cross-section, the developed curvature is reversely proportional to the moment of inertia I.

The polar moment of inertia, describes the rigidity of a cross-section against torsional moment, likewise the planar moments of inertia described above, are related to flexural bending. The calculation of the polar moment of inertia I_z , around an axis z (perpendicular to the section), can be done with the Perpendicular Axes Theorem:

where, I_x and I_y , are the moments of inertia around axes x and y that are mutually perpendicular with z-z and meet at a common origin.

The dimensions of moment of inertia are [Length]^4 .

The elastic section modulus S_x of any cross section, around its centroidal axis x, describes the response of the section under elastic flexural bending, around the same axis. It is defined as:

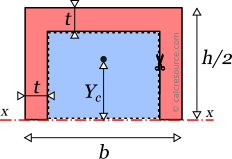

where I_x , the moment of inertia of the section around x axis and Y the distance from centroid, of a section fiber, parallel to the same axis. Typically the more distant fiber is of interest. If a cross-section is symmetric (the rectangular tube is), around an axis (e.g. centroidal x) and its dimension perpendicular to this axis is h, then Y=h/2 and the above formula becomes:

Similarly, for the section modulus S_y , around y axis, which happens to be an axis of symmetry too, the above definitions are written as:

S_y = \frac \Rightarrow S_y = \frac

If a bending moment M_x is applied around axis x-x, the section will respond with normal stresses, varying linearly with the distance from the neutral axis (which under elastic regime coincides to the centroidal x axis). Over neutral axis, the stresses are be definition zero. Absolute maximum \sigma , will occur at the most distant fiber, with magnitude given by the formula:

From the last equation, the section modulus can be considered for flexural bending, a property analogous to cross-sectional A, for axial loading. For the latter, the normal stress is F/A.

The dimensions of section modulus are [Length]^3 .

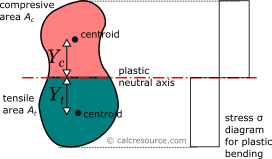

The plastic section modulus is similar to the elastic one, but defined with the assumption of full plastic yielding of the cross section, due to flexural bending. In that case the whole section is divided in two parts, one in tension and one in compression, each under uniform stress field. For materials with equal tensile and compressive yield stresses, this leads to the division of the section into two equal areas, A_t in tension and A_c in compression, separated by the neutral axis. This is a result of equilibrium of internal forces in the cross-section, under plastic bending. Indeed, the compressive force would be A_cf_y , assuming the yield stress is equal to f_y , in compression, and that the material over the entire compressive area has yielded (thus the stresses are equal to f_y everywhere). Similarly, the tensile force would be A_t f_y , using the same assumptions. Enforcing equilibrium:

A_cf_y = A_t f_y\Rightarrow

The axis is called plastic neutral axis, and for non-symmetric sections, is not the same with the elastic neutral axis (which again is the centroidal one).

![]()

The plastic neutral axis divides the cross section in two equal areas, provided the material features equal tensile and compressive yield strength.

The plastic section modulus is given by the general formula (assuming bending around x axis):

Z_x = A_c Y_c + A_t Y_t

where Y_c , the distance of the centroid of the compressive area A_c , from the plastic neutral axis, and Y_t , the respective distance of the centroid of the tensile area A_t .

For the case of a rectangular tube cross-section, the plastic neutral axis passes through centroid, dividing the whole area into two equal parts. Taking advantage of symmetry, it is: Y_c=Y_t . Finding these centroids, is straightforward. We will consider the part above the neutral axis (assumed in compression). The centroid of this part is located at a distance Y_c from the plastic neutral axis. It is convenient to assume that the whole part, is equivalent to the difference between an outer rectangle, having dimensions, b and h/2 minus an inner rectangle, with dimensions b-2t and h/2-t. The centroid of the whole part is then found, making the static moment of inertia (first moment of area), of the whole part, equal to the difference of its two rectangular areas. Remember that the examined part has half the total section area:

Taking into consideration that Y_c=Y_t (due to symmetry) and given that A_c=A_t , the plastic section modulus, of a rectangular tube, around x axis, is found:

Z_x = A_c Y_c + A_t Y_t \Rightarrow

Z_x = 2 A_c Y_c \Rightarrow

We could have reached to the same formula, a lot faster if we had as given the plastic modulus of a rectangular area, with dimensions b and h, around a centroidal axis, perpendicular to h. This is:

The whole rectangular tube could then be considered as the difference between the outer rectangle, with dimensions b and h and the inner rectangle with dimensions b_i and h_i , as illustrated in the following figure. Both rectangles share the same centroidal x axis (otherwise we could not proceed). With this consideration, the above formula is derived naturally, as the difference of the plastic moduli between these two rectangles.

Following a similar procedure, the plastic section modulus, around y axis, is found by the following formula:

Notice, that the last formula is similar to the one for the plastic modulus Z_x , but with the height and width dimensions interchanged.

Radius of gyration R_g of a cross-section, relative to an axis, is given by the formula:

where I the moment of inertia of the cross-section around the same axis and A its area. The dimensions of radius of gyration are [Length] . It describes how far from centroid the area is distributed. Small radius indicates a more compact cross-section. Circle is the shape with minimum radius of gyration, compared to any other section with the same area A. The rectangular tube, however, typically, features considerably higher radius, since its section area is distributed at a distance from the centroid.

The following table, lists the main formulas, discussed in this article, for the mechanical properties of the rectangular tube section (also called rectangular hollow section or RHS).

Outer: P_\textit = 2(b+h)

Inner: P_\textit = 2(b_i+h_i)

Total: P_\textit = 4(b+h-2t)